6. Our best Types were still not good enough

|

Wæs se grimma gæst Grendel haten,

mære

mearcstapa, se þe moras heold,

fen & fæsten.

Fifelcynnes eard

wonsæli wer weardode hwile,

siþðan

him Scyppend forscrifen hæfde

in Caines cynne. Þone

cwealm gewræc,

ece Drihten, þæs þe he

Abel slog.

|

There was this grim guest, Grendel called.

Marches, steppes

until the moors he held,

Fens and fastnesses. Wives-kin's

Earth,

Was living with the undead awhile,

Since him the

Creator fore-scribed had

In Cain's kin. Done was torturing

wrecking,

to these Thirds, for that he Abel slew.

|

|

Ne gefeah he þære fæhðe, ac He hine feor

forwræc,

Metod for þy mane, mancynne fram.

Þanon

untydras, ealle onwocon,

eotenas & ylfe &

orcneas,

swylce gigantas, þa wið Gode wunnon

lange

þrage. He him ðæs lean forgeald!

|

Not liked He this feud, as He henceforth wrecked, Meted for the

men of mankind from Then on the Untidy, all awakened:

Jœtes

and Elves and Orcs,

Such giants who with God wrangled

Long

a carry. He him that lean repaid!

|

Now what the hell is that? Sire, these are verses

from the old English poem ›Beowulf‹. The name Grendel

should be known to all readers with a little classical education and

to fans of movies too. That Anglo-Saxon poem stands at the onset of

today's English literature. It's just a crude fantasy tale from old

Denmark, and as realistic and wise as a Harry Potter book, but since

this stuff is so old and traditionally Christian, it is much more

accepted by the teacher types. The poem takes us back into the savage

mental world of the Nordic Vikings. The above verses (77 etc.) tell

us of the origin of the monster Grendel. That's the main rogue of

this poem. The poem has it that Grendel was a monster that lived in a

water cave. At night it entered the houses to feed on sleeping men.

Now, isn't it a great idea to have such people with us, from the

modern point of view of diversity?

The ghastly world of the poem of Beowulf is replete

with monsters, and these are all bad beasts who need to be slain by

the hero. Noteworthy is that this poem also counts in Jœtes and

Elves, and Orcs of course. Jœtes are in principle the people

from Jütland, that is Northern Denmark. But here the name rather

means mythical bad giants, like those known from the Bible and the

ancient Greek religion. Like Elves or Orcs they don't appear in this

fantasy tale. Instead the hero Beowulf mainly fights with marine

monsters. The name Grendel reminds of our word green, and indeed it

sounds likely that the name means Green One, reminding of the Arab

fantasy saint al-Khidr. This good spirit of vegetation fits much

better into our real world, as seen by the UTR. In fact there are

angels, gigantic good aliens who help us not only with odd fantasies.

Some of the Ranoids, who descended from frogs, indeed have green frog

skin. When our goddess Ga-Jewa was still space-bound, dwelling among

undead Greys, and later when Ewa created her Earth, Ranoids helped

her with emotional support. In our fantasies they occasionally

represent the evil aliens too. That help allows it to the gods to

control fantasy figures and let real badies die faster.

In the real world, feuds and mischief would wreck

so many young lives in the North. Bitter traces of these tales can

also be found in the poem ›Beowulf‹. There was the

story of Hygelac, one king of the Gauts from Southern Sweden. As a

Viking he sailed, to raid Frisia and North-Deutschland. Around 516 a.

he was killed by the Chattuarians. Hygelac was famous for his size.

After his death they exposed his bones. As a "giant" he

appears in a ›Book of Monsters‹. Jœtes (Deutsch:

Jöten) was one of the traditional names given to giants.

That name denoted the inhabitants of Jütland in Northern

Denmark. Around the year 450 a., Hengest had sailed from there with

three warships to win land in England. Not much later those

Anglo-Saxons overpowered the Romano-British lords and men of king

Vortigern, by a treacherous assault. Kent subsequently was conquered

by these Jütlanders. Others also won the rest of the British

Isles. In principle Hengest could have become a famous national

founder and hero of Anglo-Saxon Britain, maybe comparable to Julius

Caesar. But another story of Hengist shows him as a guy too mean for

that, an outlaw who broke oaths. The saga of the battle of the

Finnsburg has it that Hengest was spending the winter there with his

war band (432 a. ?). Peace had been made with the Frisians after a

stalemate raid. But early next year Hengist killed his host Finn, and

abducted duchess Hildeburg with much booty. The poem tells a shocking

truth: Even our big, fair, sly Nordic men may not be good enough to

resist to evil!

Today's scholars explain the ruthless and

battle-happy Vikings with the notion that these had still been

pagans. However, later Christians like the Frankish king Chlodwig,

often were even more treacherous and ignoble. Wyrd, the power of

destiny, played so mean tricks on them! In principle they believed

that the gods were protecting them. The gods should see to it that

oaths were kept and mishaps avoided. But such good hopes did not meet

the reality of tricky and cruel destiny. We may think of the

half-mythical Beowulf as a Nordic seer. In dreams he did let his mind

wander, to find out who was out there. Who made this bad destiny for

them? Beowulf did not envision Nordic gods. He met monsters in

strange wildernesses. The tale has it that Beowulf battled nightly

monsters of the sea, that he was killing strange sea-monsters. The

poem boasts that Beowulf was the son of Eggtheow, the king of the

Gauts. But an older tale has it that his mother was the servant maid

Bera, who was made pregnant in the night time, by a man wearing a

bear's hide.

So that was the reason why in the poem Beowulf had

no other kinsmen but his "uncle", the king. The main tale

of the epos ›Beowulf‹ has it that Beowulf killed the

troll Grendel and his mother, who lived below a cliff and were

devouring the men of the Danish hall of Heorot (today: Lejre). Some

scholars put this mythical feat into the year of 512 a. But that was

the exact time when the Hadubarden of Ingjald took revenge there.

Breaking peace oaths and marriage bonds, they fought with the royal

Danes until their hall went up in flames. Of course there were no

nightly monsters, who sowed misery and doom, just because they hated

it when the guys in the hall drank mead all the time and cheered

happily – or were there? The UTR warns before the nightly

attacks of the N-rays from outer space. The Greys who are angling

with rays notice it, when people down here get too lazy and depraved.

They may put bad ideas into their minds, and force them on

disrespectful ways, or just make them get sick and old faster. The

epos also fantasizes of the fight of Beowulf against a dragon. Often

this beast is called a night flyer, who spits fire down from the sky

that sets halls and huts ablaze. For such mishaps the Greys tried to

blame the Earth Goddess. She too was eventually regarded as a dragon

or a reptile monster, since she originates from a planet where not

humanoids but reptiloids were the intelligent species. At times the

Earth Goddess even appeared as a dragon-lady of dawn, announcing the

sure coming of her messiah, symbolized by the Sun. Her gigantic halls

down in the deep are full of machines and artful pieces. When it is

written that she is a poisonous dragon, that refers to the special

climate of her Betyle that men cannot survive. She also heeds lots of

lost treasures from times long gone, for me to retrieve them some

fine day.

In one book about Medieval literature I read about

the famous Hunnish king Attila. He engaged Germanic bards to sing his

praise. But of his Asian cruelty remind the horrible Icelandic songs

of Atli. Truly the peoples of Europe called him "the scourge of

God", since he had been so bad and savage and belligerent. From

the modern point of view of diversity, some dopey guys would even

welcome the Huns, surly ready to part their property with these and

their sluts too, hoping that this would render Europe racially more

diverse. But when the Christians raise and spread migrants of such

hated sorts, it's not because they hope that these will enrich our

cultures. Their idea is it that God sends these to us for a reason.

These are supposed to bring us down, and to turn this fairly nice

world into a hell of depravation – a planet that would be ready

for doomsday. We find this basic idea of hereditary sin and divine

revenge nicely explained in the above cited lines of the poem

›Beowulf‹. For the death of Abel, allegedly the Creator

took sore revenge on all humankind. Allegedly God created monsters to

avenge, including those with a human body.

Wasn't even Hengest, this most renowned hero of the

Anglo-Saxons, some kind of monster man? In the poem ›Beowulf‹

we often read about a bad superstition of that era. Again and again

boars and piglets are mentioned there. Pig images adorned many a

helmet, armour or sword. They were supposed to bring luck to the

people who wore them. Due to a feud over Sviagriss, a ring adorned

with a piglet, the proud realm of the Gauts was destroyed. At last

the UTR now warns before the bad magic of the Feken. Due to my

warnings, many boar-head stickers disappeared from our cars.

In the poem ›Beowulf‹ the mythical

Biblical hero Abel replaced Balder, the Germanic god of light. He

stands for a fair hero who didn't make it, who died to then let a

deluge come. The Greys would indeed use such a cataclysm, to try and

create mischievous monsters.

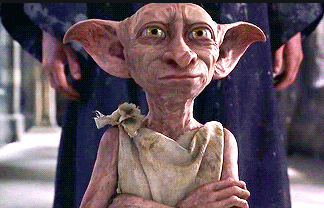

This

odd image shows the Elf Dobby. It's from a Harry Potter movie. The

rather dark saga of this sorcerer apprentice was created by the

British author J. K. Rowling. If we search for cultural stuff that

has shaped and reshaped not only the culture of Britain, then surely

this saga needs to be mentioned. For many it's just entertainment.

But is there more to it than Harry Potter readers and movie

spectators may be able to believe? Surely the answer to the question

depends on whether magic truly exists or not. From the point of view

of the UTR, it is absolutely correct when Ms. Rowling wrote about

muggles, "normal" people who can neither see magic nor

believe in it.

This

odd image shows the Elf Dobby. It's from a Harry Potter movie. The

rather dark saga of this sorcerer apprentice was created by the

British author J. K. Rowling. If we search for cultural stuff that

has shaped and reshaped not only the culture of Britain, then surely

this saga needs to be mentioned. For many it's just entertainment.

But is there more to it than Harry Potter readers and movie

spectators may be able to believe? Surely the answer to the question

depends on whether magic truly exists or not. From the point of view

of the UTR, it is absolutely correct when Ms. Rowling wrote about

muggles, "normal" people who can neither see magic nor

believe in it.